Daniel Arnold currently has two books out. I thoroughly enjoyed reading both of them. His first book, "Early Days in the Rage of Light", is an excellent read covering the first ascents of several major peaks within the High Sierra. Arnold covers the historical aspects of each climb, while painting vivid portraits of the personalities that first explored and climbed in this region of the Sierra Nevada. The most unique element of Arnold's telling of the story is that he followed in the footsteps of these early mountaineers, climbing the mountains as they climbed them, thereby retelling from personal experience some elements of these early adventures.

I was torn on whether to write a review on Early Days in the Rage of Light, or Salt to Summit, which has a similar style. I ultimately chose Salt to Summit because it's the story of a journey I have thought about long before ever hearing of this book. It's a journey that has now been taken by many folks, in many different ways.

California has the unique claim of containing both the lowest and highest geographical point in the contiguous 48 states. Bad Water in Death Valley at -282 feet is the lowest point in the US (and in the Western Hemisphere!) and Mt Whitney at 14,505 feet is the highest point in the lower 48. They are separated from each other by only 85 miles, as the crow flies!

I don't know who did it first, but it was only a matter of time before somebody had the idea of climbing Whitney starting from Bad Water. I've always wanted to go from Bad Water to Whitney Portal by bicycle and then hike/climb Whitney on foot from there by way of what's called the Mountaineer's Route, all taking place over 2-3 days.

Arnold has done this journey by what I think is probably the most adventurous way I have heard of yet: on foot, the whole way, depending mostly on natural water sources and going out of his way to trek up and over peaks and high crossings of intermediate ranges, exploring deep canyons and avoiding as much as possible dirt roads and even foot trails. All the time, he covers the historical aspects of the areas he travels through and retells the stories of those that have come before him.

I was inspired. Both, to stay focused on my desire to do my own (much easier!) version of this journey, but also by the history and people that have occupied and visited this land over the years. Also, I realized I had been, in bits and pieces, to many of the places along his route already and could dress up a review of this book with some of my own photographs.

(I marked my photos with ET. I got the historical ones off the web and don't know whose they are. If you own one of them and would like credit, please contact me.)

Bad Water to Tucki Mountain

|

| Some of the "Bad Water" at Bad Water ( ET) |

Arnold starts the adventure by utilizing a combination of bus rides and hitchhiking to get to Bad Water in Death Valley. In order, to experience a tiny taste of the more extreme weather at the beginning and end of his journey he chose to start in April, which is just the right timing to experience some early summer 100+ degree weather in Death Valley, while still getting a taste of winter in the Sierra on Mt Whitney. He definitely wasn't trying to do this the easiest way possible, that's for sure.

Bad Water is a tourist attraction. Both the highest recorded air (134 deg) and ground (201 deg) temperatures in the world were recorded nearby at Furnace Creek. It is situated up against the Black Mountains, which tower over 5000 feet above the lowest place in the Western Hemisphere. From there, salt flats stretch into an expanse of nothingness, right up until your vision hits up against an 11,000 foot wall called the Panamint Range, on the far Western edge of Death Valley. Most tourists will walk out a short ways on the salt flats at Bad Water, until they realize they're getting nowhere fast and start to feel the heat not only beaming down from above, but baking them from below, as the sunlight reflects off the bright, white salt. I could imagine some of them watching Arnold walking further on with his 80 pound pack, until he slowly faded into the heat shimmers and eventually disappeared into the landscape altogether. On the way back to their air-conditioned cars, they must have thought, "Where the hell was that dude going?"

|

| Salt Flats near Bad Water ( ET) |

I will leave out most of the details of Arnold's personal journey, so as not to spoil his story, but will summarize some of the history of the area. The book contains many more details, additional stories and colorful characters.

On the way to Shorty's Well on the western edge of Death Valley across the Salt Flats, Arnold tells of a small group of 49'ers, which were the first "whites" to set foot in Death Valley. It is not a happy story. Some of them died. All of them suffered. They were a smaller group of a much larger wagon train traveling along the Old Spanish Trail, on the way to what is now the Los Angeles area. They were the ones that were lured by a vague tale of a shortcut on a mysterious map that surfaced amongst the wagon train. The leader of the wagon train ominously warned them that, rather than cut off 500 miles, "the shortcut would more likely lead right to Hell".

As the 49'ers who arrived in Death Valley started to realize the trouble they were in and panic and desperation started to grow, they broke into smaller groups. One group consisted of the Arcane and Bennett families and, along with them went the hero of this story, William Lewis Manly. Like with the rest of the 49'ers, things got desperate for the Arcane and Bennett families. They headed south through the valley and ended up stranded near the base of the imposing Panamint Range, at what is now called Bennett Spring. Manly was young, strong and in his prime. He could have easily abandoned the two families and saved himself. But, he did not and stayed with them as a loyal friend. In fact, when he was finally asked, he traveled over 250 miles to Los Angeles for provisions/supplies and all the way back, risking his own life in doing so. He then led the families out of Death Valley, in essence, saving all their lives. However, the only reason any of them survived was that they showed up in January. If it was even slightly later in the year, this could have been an entirely different story.

|

| Artists Depiction of the Manly/Arcane/Bennett Party in Death Valley, the Panamint Range Looms In The Distance |

I've visited two areas along what is now referred to as The Escape Trail - the path which Manly took while rescuing the Arcane and Bennett families. They are both in remote, rugged areas, even today. But, what a difference a 100 years make. I visited both of these areas on my dirt bike, with supplies a short distance away in my 4Runner, which was parked near a paved highway, even if a rather lonesome highway. The first plaque on the left in the image below is in the Slate Range. The canyons on either side of the crest - Isham and Fish Canyons - are both named after 49'ers that perished there. The other plaque is at the crest of the Panamints at Rogers Pass. It is here that either Manly, or John Rogers who accompanied him, took off their hats, looked back and exclaimed, "Good-bye, Death Valley", first providing this place with perhaps a very fitting name. As Arnold points out, they likely had the beginning of the prayer, "Yea though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death", in their minds.

|

| Memorials Along The Escape Trail ( ET) |

|

| Panamint Crest From Middle Park ( ET) |

|

| Butte Valley ( ET) |

|

| William Lewis Manly |

From Shorty's Well, which is right near Bennet's Well, Arnold goes north through Death Valley, without actually visiting Middle Park and Butte Valley, or the Slate Range. He was, after all, on the way to Mt Whitney, and needed to resupply at Stove Pipe Wells.

Along the way, he also tells the story of another individual - George Hansen. What none of the 49'ers knew at the time was that they were all being watched. They were being watched by the native inhabitants - the Shoshones - that had been living in Death Valley since long before the 49'ers showed up. They knew how to live off the land, seasonally traveling between the valley in the winter and high up in the Panamints in the summer. George Hansen was a young Shoshone boy when the "whites" first arrived in the valley. He and his father could see the 49'ers burning their wagons from high up in the Panamints one night. They traveled down to the valley and could tell they were sick and in trouble. But, they also feared these strange interlopers and, so, they stayed clear, watching only from a distance.

Tucki Mountain to Stovepipe Wells

Tucki Mountain ranks up with some of my favorite peaks in Death Valley. I did this hike a little ways back from Skidoo - a route which popular guidebook author Andy Zdon calls an "epic route". I'm not sure why, as he has several hikes that are more difficult in his guidebook. Regardless, on his way to Stovepipe Wells, Arnold decides to go straight up and over Tucki from the valley floor, taking what is undeniably the truly epic way to hike Tucki! If I understood his route, he would have crested out on a ridge above and near this little valley I had to cross on my way to Tucki. What he probably missed, however, was the neat little cabin barely visible in the photo below. Can you spot it? At one time, a lonesome miner called that his home.

|

| Old Martin Crossing ( ET) |

Arnold spent the night on Tucki, before heading down the following day. From the summit of Tucki, one can see the crest of the Sierra in the distance. I'm glad I still didn't have to hike to Whitney, as the view would have thoroughly discouraged me. Whitney looks far way in the West, sitting on top of the jagged, snowy Sierra crest, with multiple dry, rugged desert ranges in between that need to be traveled over. Although, he made no mention of it, I personally found the benchmark on the summit, which was named "DEATH", rather ominous, when I was out there on Tucki all by myself. Perhaps, Arnold found the view to Whitney a bit more ominous - I know I would have.

|

| Tucki Summit Benchmark, "DEATH" ( ET) |

Cottonwood Mountains to The Race Track.

On the way to Stovepipe wells and then off to the Cottonwood Mountains, Arnold expressed a thought I have always wondered about myself. The miners that stayed in Death Valley had to be there for more than the gold. The desert is a rough place and there has to be an easier way to make a buck. Perhaps, this saying from the classic move Lawrence of Arabia sums it up best

"I think you are another of these desert-loving English. No Arab loves the desert. We love water and green trees, there is nothing in the desert. No man needs nothing."

John LeMoigne, Shorty Harris and some of the early Death Valley personalities must have had much in common with those desert-loving British, like T.E. Lawrence, because they came to Death Valley and stayed.

LeMoigne stayed in Death Valley for many years, until perishing under a Mesquite with his burros. He had a lead-silver mine he long maintained in a canyon that now bears his name. LeMoigne also had prospects scattered all across the desert and was credited as having a "kind of mental diviner's rod" for finding ore. Surely then, if any man could have "struck it rich" and left Death Valley to live in style, it was LeMoigne. But, he mostly worked his lead-silver mine and only just enough to subsists and survive. Like Arnold says, maybe he was poor and stubborn, or maybe he liked being monkish. Either way, his mysterious ways turned him into a local legend and Death Valley must have held an attraction for him, which kept him there the rest of his years until that fateful day under the Mesquite bush.

|

| John LeMoigne In Skidoo |

Arnold has a great Shorty Harris quote in his book: "Who the hell wants $10,000,000. It's the game man - the game". Harris first found the famous Death Valley site called Bullfrog, with his partner Ed Cross. They found a piece of ore in the vicinity and knew the ground was rich in gold. They went off to Goldfield sixty miles away to register their claim. In town, Harris flashed his ore at anyone willing to buy him a drink and within no time started the rush of all Gold rushes. Shorty Harris was not part of the rush on its way to Death Valley. He was still in Goldfield in a full swing drinking binge. When he finally came out of his drunken slumber 6 days later, he found that he sold his claim to Bullfrog for $1000 to the bar keep. His partner, Ed Cross, made enough money to buy a 120-acre walnut and orange farm near Escondido. Harris ended up right back in Death Valley, where he spent most of his time for the next 40 years of his life, repeating similar patterns. So, was Harris an irresponsible drunk? Or, was he in it for the "game"? Did he just love life in the desert? Either way, add his name to the list of those enigmatic characters, which the history of Death Valley seems to be full of.

|

| Shorty Harris and His Mule |

Arnold visits several areas along this route that I wish I had better photographs of, but don't. We took zero photos when we were in Cottonwood Canyon. We never found the petroglyphs in Marble Canyon. And, we haven't even been to the Ulida Flat area, yet. I have been to the Racetrack, but was dumbfounded when I realized I had only one crappy picture of the sliding rocks. Clearly, I need to return and visit all these areas.

Arnold calls the Racetrack the "strangest place he has ever seen". I didn't realize how flat it was, as it rises only 1 inch over its 3 miles of length. Rocks move across this flat leaving strange tracks in their wake and nobody knows why, or how, this happens. Countless teams have been there to study the rocks and the best answer is gale force winds combined with rain and icy conditions. To this day, nobody has ever witnessed a rock move. Death Valley is full of magic and mystery!

Saline Valley and Up and Over the Inyo Mountains

|

| Saline Valley Dunes, Inyo Mountains ( ET) |

I've always held the stories of the earliest miners and settlers to the West with great fascination in my mind. I think one area that has done that more so than many others is Saline Valley and the Salt Tram on the crest of the Inyos. Saline Valley is a remote place, even today. Some consider it one of the most remote spots in the lower 48 and Zdon calls the canyons on the Saline Valley side of the Inyos, "some of the most rugged canyons in the United States". Rebecca and I came to Saline Valley a few years back to climb Saline Peak. The middle of Saline Valley takes about 40 miles of dirt road to get there, regardless of the direction from which one comes. Saline Peak requires another 11 rough miles of 4x4 up a corridor on the eastern edge of Saline Valley. How much more remote was this place back in the early 1900s?

|

| Saline Valley, Inyo Mountains ( ET) |

Saline Valley sits at just over 1,000 feet in elevation and the crest of the Inyo Mountains range anywhere from 8000 feet to over 11,000 feet at some of the higher peaks. Men came to Saline Valley, not only for gold, but mainly for salt. But, the challenge they faced was how to get this salt out of Saline Valley. The answer they came up with was a Salt Tram situated atop the Inyo crest at 8700 feet that would transport the salt over 7700 feet up from Saline Valley to the top of the Inyos and then back down over 5000 feet to the other side in Owens Valley, crossing some of the most rugged canyons and desert landscape the west has to offer and all back in the early 1900's. What an engineering feat! Not too mention the labor. Every piece of the tram, from the 54 miles of steel cable, to the 1.3 million board-feet of lumber and the 650 tons of nuts and bolts had to be carried in on the backs of mules. An additional temporary tramway had to be built just to transport supplies and water in support of the main tramway construction. It's no wonder, the whole salt adventure never really payed off and the salt tram exchanged hands many times over before eventually being abandoned altogether.

I visited the Salt Tram during the China Lake 350. This location on the Inyo Crest seemed surreal that day. We were in a race with some minor storm clouds and fading daylight on our way down the Swansea Grade, as snow flurries dropped around us. I'd really like to go back, take my time and check out some other areas up there, as well. Not a very easy place to get to, though. It's a pretty airy and exciting 4x4 and, even as a dirt bike ride, there is a small challenge, or two.

|

| View Down The Cable Leaving Salt Tram Station Along The Inyo Crest ( ET) |

|

| Saline Valley Down Below, As Viewed From Salt Tram Station On The Inyo Crest ( ET) |

|

| Historical Photo of Salt Tram Construction |

It's stories like the one of the Salt Tram that leave me fascinated. But, Arnold's book taught me something I was naively unaware of. Just like the Shoshone in Death Valley, the Saline Valley was already populated before "white gold" was discovered and their land was invaded. I just come to these places as a hobby in my spare time and extended periods away due to injury leave me feeling down. About 30 Shoshone lived near Hunter Canyon in Saline Valley, but were eventually displaced. The land was part of their soul and their soul was part of the land. They were there when the land was pristine and free. It's hard to imagine the pain they felt when they were pushed off. Now, at least I know the whole story. Manifest Destiny, which drove the relentless march westward, also reached this remote corner of the country, with its tales of tragedy. In retrospect, I should have known this must have happened.

Arnold goes on to tell the story of his journey across Saline Valley and up and over the Inyos. I won't spoil any of the details, but suffice it to say it was probably his spiciest adventure of the whole journey!

Owens Valley to Mt Whitney

The history of Owens Valley was once again one of the "whites" coming in and displacing the local Indians - the Paiutes. The original settlers in Owens Valley were mostly farmers and ranchers and skirmishes with the Paiutes happened on a regular basis. However, history here has a bit of an ironic, if not almost karmic, twist to the story. Several years later, Los Angeles started to boom and the city got thirsty. William Mulholland helped to build the Los Angeles aqueduct, which slowly siphoned the water from Owens Valley and sucked it dry for any decent farming. Now, it was the local farmers and ranchers - the "whites" - that were rebelling by dynamiting the aqueduct and even taking over the Alabama Hills Spillway. Eventually, the farmers and ranchers were mostly displaced. There is still some farming in Owens Valley, but nothing like it used to be. Owens Lake is all but gone, looking more like a dry lake bed most days. The wind regularly kicks up dust storms off its surface.

Arnold tells of this history as he descended from the Inyos and made his slow trek across Owens Valley on his way to Lone Pine, before a quick resupply. He then headed out for his final destination - the summit of Mt Whitney.

|

| Mount Whitney From Near The Summit of Thor Peak ( ET) |

|

| Rebecca on the Ebersbacher Ledge System, On a Trip Up The Cleaver Col Drainage ( ET) |

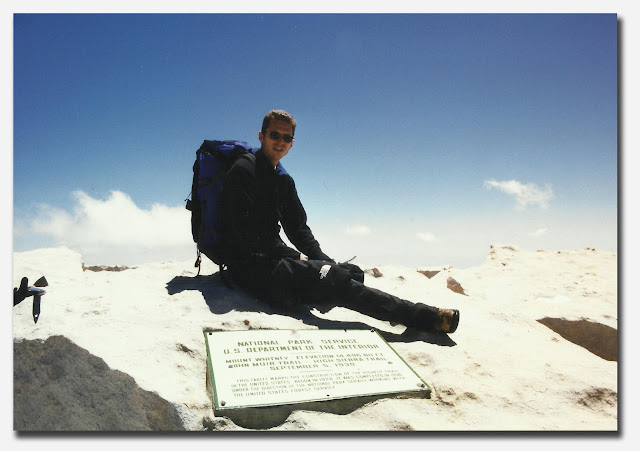

Reading Arnold's book made me think of looking through our old photo albums, from the days before we owned a digital camera. I came across this print of myself from when Rebecca and I first climbed Mt Whitney via the main trail in 1999. Pretty recent history, but digging up this slightly faded print from our old albums of a trip that seems so long ago, almost made me feel like I was looking at one of the historical photos from this blog! I've avoided Whitney like the plague since then. Mainly because I don't like the popularity of the peak and the crowds, preferring to go to less crowded summits and also to simply explore new areas we haven't been to yet. Now, I'm inspired to go back. I honestly don't know if I can pull off the Bad Water to Whitney journey anymore, but I definitely want to try. At the very least, I would like to follow the author's footprints up the Mountaineer's Route. (And, perhaps in better style than last time. Hard to tell from the photo, but I am close to losing my lunch)

|

| Me On Whitney, 1999 ( ET) |

Salt To Summit is a great read and I highly recommend it. If the romance and adventure of the early West and outdoor adventures stories, in general, hold any personal appeal, I think one would enjoy this book. Arnold's vivid language and his unique approach to telling the stories by reliving them as best he can, makes for a heartfelt and lively story.

Daniel Arnold, Salt To Summit

References

** Andy Zdon, Desert Summits

** Michel Diggonet, Hiking Western Death Valley National Park

No comments:

Post a Comment